The relationship of the gospel to prosperity is a controversial topic. Some claim that God promises material blessings to the faithful, others deny the materiality of blessing altogether. And, of course, there is a range of views in between.

Psalm 128 is a rich and beautiful poem that gives us anchors for understanding prosperity in God’s economy.

A Literal Translation

1 A song of ascents.

The good fortune of everyone who fears the Lord

Who walks in his ways.

2 The labour of your hands surely[1] you shall eat

Your good fortune

and good (things) to you.

3 Your wife like a fruitful vine

In the recesses of your house

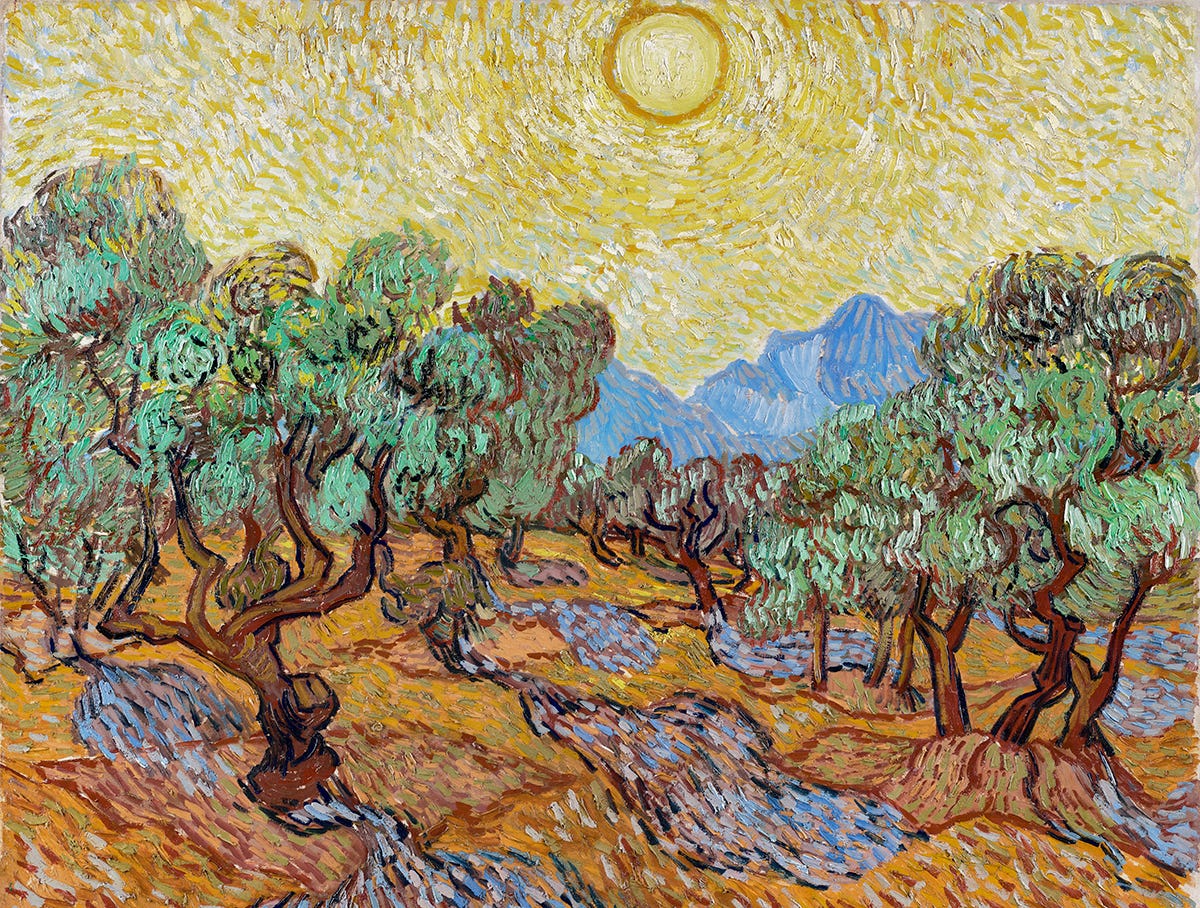

Your children like olive shoots

Around your table.

4 Behold, surely thus shall the man be blessed who fears the Lord.

5 May the Lord bless you from Zion

(That you)[2] look upon the good of Jerusalem

All the days of your life.

6 (That you) see the children of your children.

Shalom upon Israel.

Verb Shortage

Hebrew often implies a “being” verb without using one, which in Psalm 128 leaves us with a lot of nouns and a lot of options. English translations understandably try to add these verbs in, which makes definite things that the Hebrew text leaves ambiguous. Should “Your wife like a fruitful vine” be read as a description? A promise? A hope? Your Bible’s translator will have decided on one, but the Psalmist didn’t.

This immediately confronts us with one of the infuriating and beautiful things about biblical poetry: it leaves open matters that we’d sometimes like a little more closed. Psalm 128 is especially happy to sketch a picture and let us fill in some of the lines.

I have attempted to capture in my translation the effect of leaving out so many verbs. To me it sounds like a beatitude or a toast: it’s a list of short but expansive declarations of the good life for Israel.

Wasting a Wish?

Of all the wonderful things that might top this list, the first blessing might seem underwhelming: May you get to eat the food that you worked for.

When you think about it, though, what is worse than having nothing to eat, and working hard only for someone else to take what you earned? “The fallow ground of the poor would yield much food, but it is swept away through injustice” (Prov 13:23).[3]

The blessing of eating the fruits of your labour implies two wonderful things that we tend to take for granted until they are gone: In the first of a series of nods towards Genesis, it means that you have been spared the worst of God’s curse on the ground, and it means that injustice has been sufficiently curtailed that your wages are still yours.

Family Man

The second blessing is directed at family – a fruitful wife and a bustling dinner table. If, again, regular pregnancies aren’t on your divine-blessings wish list, it’s worth appreciating some of the hints of the wider goodness involved here, such as “fruitfulness” being suggestive of more general abundance (cf. Prov 31), the absence of loneliness, or the fact that this is a home of such size and calm as to have recesses into which the family can retreat.

But more importantly, in Genesis 3, God pronounces trouble upon both the ground and the womb. The archetypal domains of male and female are cursed in Genesis but blessed here. This blessing is good not because big families are always desirable but because it means the resurrection of all of humanity’s stillborn hopes.

Two Kinds of Blessing

While the noun ’ashrei (“good fortune” or “happiness”) dominates verses 1-3, verses 4-6 feature the verb barak (“to bless”). While the former describes a state of being, the latter is best understood as an expression of divine favour.[4]

We might be forgiven for getting caught up in the psalm’s material blessings, but barak brings our focus back to the divine Giver. Verses 1 and 4 bookend the description of this blessed Israelite with relational and covenantal ideas: favour with God, fear of God, imitation of God.

Perhaps here again we have notes of Genesis, in which we were created to image God and to walk with him. Even if not, it underlines that the ideal Israelite is firstly a person who desires to share God’s character and to walk in God’s footsteps. Blessing is what flowers within a right relationship with God.

Whose Shalom and When?

The last two verses echo the same blessings (repeating “good” and “children”) culminating in a wish for the shalom of Israel. “Shalom” is prosperity language that encompasses peace, health, happiness and more. We often translate it as “wellbeing” in an effort to capture its breadth. In verse 5, the blessings now come from Zion.

Our present connotations with Zionism may distract us from the better associations that are at work here – again from the early chapters of Genesis. Zion or “the city of God” is regularly connected to “garden of God” concepts, and links to Eden are common in Zion theology (e.g., the rivers of Gen 2:10 and Ps 46:4).[5] In the Old Testament, prosperity is regularly circumscribed by both relationship and place, as hinted at here. Blessing operates within right relationship with God and the temple-like sacred spaces in which God meets his people. Prosperity achieved outside of God’s order is not necessarily a blessing and may even belong to the curse.

Finally, depending on whether the psalm was written pre- or post-exile, these latter verses may be especially poignant. Zion theology gained force after the exile because it expresses a yearning for Israel’s full restoration. Pictures of blessing such as this one might have been as much an expression of loss as of expectation, given that the enjoyment of one’s labour and the security of one’s life were far from guaranteed in occupied Israel.[6]

As a psalm in the mouth of people in exile, or scarred with its memory, it takes on the tone of a plea that once again they might ascend Mount Zion and feel streams of blessing flowing out of God’s dwelling-place among them.

Your Wellbeing and Mine

The blessings in Psalm 128 are modest and earthy, but behind their materiality, they express no lesser hope than in the defeat of the curses that beset humanity at the fall. Furthermore, against the backdrop of Israel’s exile, this poem came not to express what is owed us as believers but what can so often elude us. It expresses hopes that are anchored in the story of fall and redemption, and a prayer for God’s presence to be among his people. In this way, blessing in the OT is deeply spiritual.

As NT people, we often spiritualise away the materiality of God’s blessings in an effort to divest our hopes of any worldliness. However, Paul’s reference to “every spiritual blessing” (Eph 1:3) likely doesn’t mean that our blessings are immaterial as much as that they belong to the coming age.[7] The difference between blessing in the OT and NT is not one of materiality versus spirituality, but rather a change in the environment of relationship in which God intends to offer the fullness of his blessings. The Old Covenant was not capable of creating in Palestine a place of divine-human relationship in which love was unbroken and hearts did not stray. The incarnation of Christ created a new way of discipleship in which we are indwelt by his Spirit who rewires us from within, but even for us, every “now” comes with a “not yet.” While we now have a foretaste in the church, the creation of this place of blessing is still in our future.

Affirming the materiality of blessing is right because we are invited not just to know the Lord’s goodness but to taste and see it in a full-bodied way. At the core of God’s character is his unreserved favour and generosity, but as a people still prone to corruption, our eyes can even now be turned toward the gifts rather than the Giver. God is at work to fulfil our ultimate good, not merely to meet our lesser desires. It is only in the new creation, at the end of our long perseverance, with relationship unhindered, that we’ll dwell fully within God’s shalom.

Dr Jordan Pickering is Director of Media at KLC, an Associate Editor of TBP and an Associate Fellow of KLC.

[1] Or “When you eat the labour of your hands, happy are you.”

[2] This construction can express a promise. See John Goldingay, Psalms, Volume 3: 90-150 (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 512.

[3] Regarding this kind of blessing, Ecclesiastes 2:18-26 agrees that there is “nothing better.”

[4] In my evaluation, this was persuasively demonstrated in C. Mitchell, The Meaning of BRK “to bless” in the Old Testament (Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1987).

[5] See H.-J. Krauss, Theology of the Psalms (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 1986), 80.

[6] See, for example, Nehemiah 9:36-37.

[7] In the same way, Paul says we will be raised with a spiritual body, which means an “imperishable” one or one that is “of heaven,” not meaning one that is “ghostly” or “immaterial” (1 Cor 15:35ff).