The ubiquity of the phrase, “Just Google it,” reveals a great deal of our cultural moment. Wondering how many grams are in a cup of flour? “Just Google it.” Unsure of which train to catch in order to get to your destination the fastest? “Just Google it.” Faced with a piercing and difficult question from a child? “Just Google it”?

With my current class of seven-year-olds, we go for biweekly nature walks. On these we encounter all manner of things to see, to touch, to hear, to feel. Some are familiar – the horse chestnut, the brook we cross over. Others are more novel – a crested bird, something peculiar on the ground, an unknown call from a tree nearby. Occasionally, we come across things that neither the children nor myself can identify. The most straightforward solution to this seeming incomprehension is, of course, the solution for all of our other queries and questions. “Just Google it.”

This approach is neither the best for the child in that very moment, nor in the long term. Learning, in our modern age, is something that evangelists for the digital movement say has never been easier. Languages near and far, ancient and modern, can be accessed and purportedly mastered with an instant download. Previously exclusive courses can be accessed, videos on all manner of topics watched, questions answered.

Yet learning, like all kinds of formation, is not something that comes easily. The great thinkers of the past understood that learning requires effort, difficulty, discipline, and it happens far slower than we might like. As the Victorian educationalist Charlotte Mason puts it, education is “the discipline of habit.”[1]

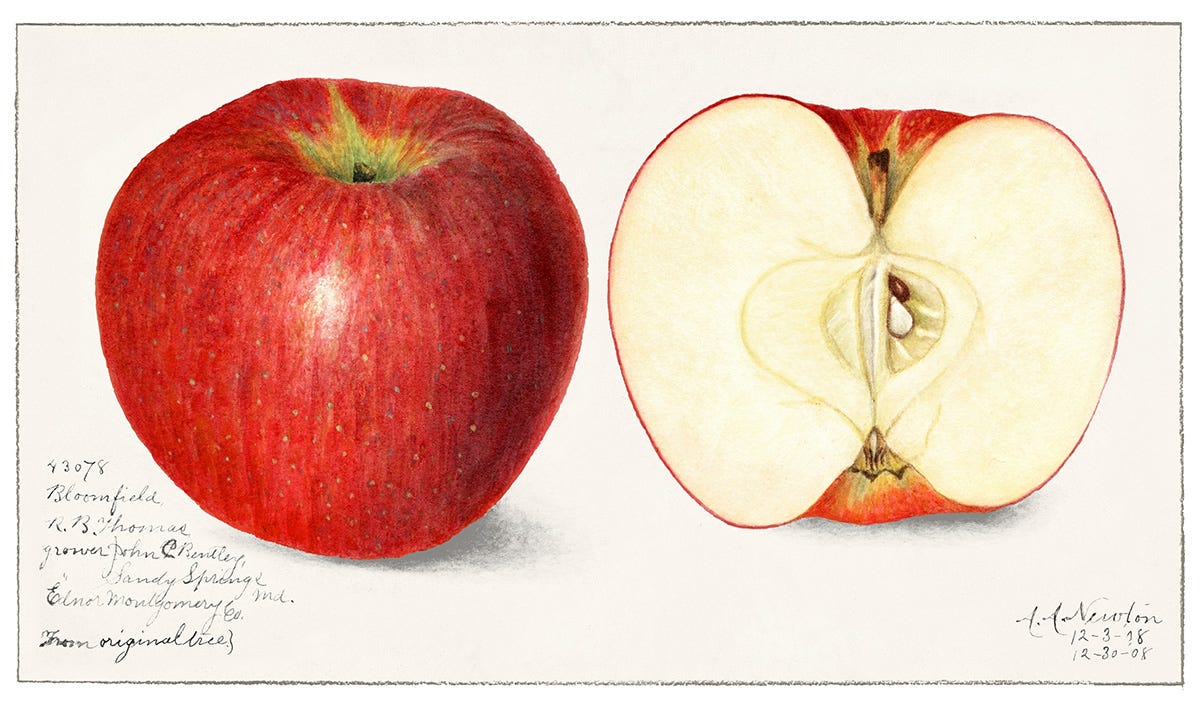

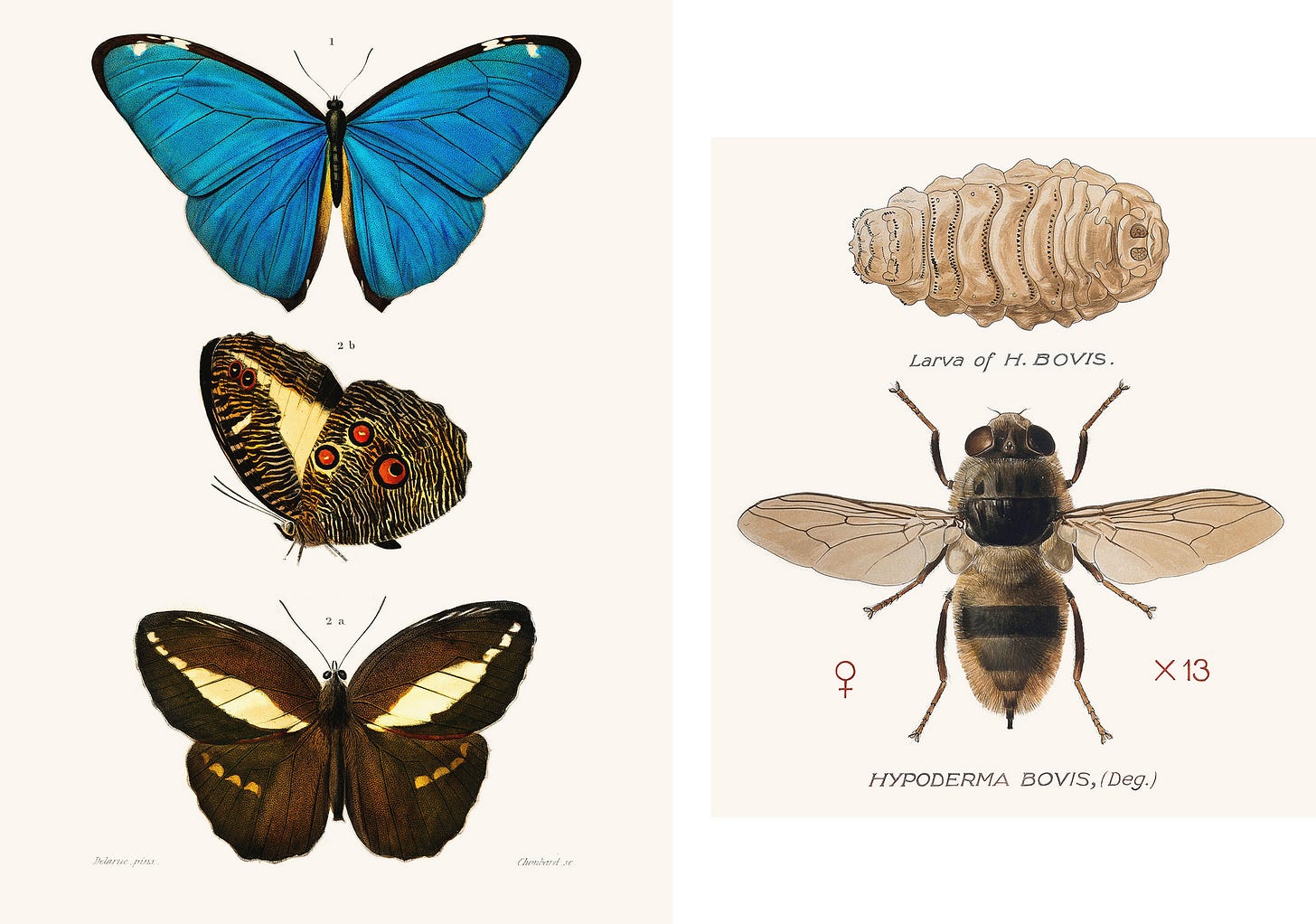

In our school setting, instead of relying on the instant benefits of the digital age, we encourage consulting guidebooks and encyclopaedias. The wonders of these tools of learning are that they require your attention and force of will. You really need to look at your leaf, or your flower, or your eggshell. How many fronds does it have? Is it variegated or not? Speckled or smooth? How we perceive the depth of an object depends on our abilities to patiently and deliberately attend to it. These processes of discernment require our energies and our agency. Furthermore, it may also be that you encounter other stimulating and gripping pieces of information. While flicking to find “London Plane,” you will also stumble across “Larch” and “Lime.” There are other avenues of curiosity to pursue, other things that may pique your interest and draw you toward them. This is real, exciting learning that feeds the curious mind of a child.

The thing that, I believe, is most harmed in our digital age is our power of attention. I have spent some of the last two years thinking about attentional malformation, and the manifold ways that the digital age warps and re-designates what it even is to attend to anything at all. In the paradigm-altering work, A Web of Our Own Making, Antón Barba-Kay[2] asserts that the whole structure of the internet is essentially set up to capture, and inevitably monetise your attention. This, of course means that our digital devices impoverish our capacity to attend to things well. Barba-Kay makes the claim that not only does digital technology make it harder to attend to something, but it more perniciously reveals to us that we would much rather be satiated online than sustain attention to anyone or anything. Barba-Kay claims that our natural state is the effortless desire for absence. The mind, online, is directed toward no end at all. Near the conclusion, he states boldly: “digital technology is spiritual opium.”[3] We are hooked.

This is not a healthy backdrop in which children can be formed well in the educational sphere. The evangelists of the digital age would have it that nearly all our teaching be conducted with a nod to the technologies of the future. In my short time as a teacher, I have seen things such as PE lessons that have children inside a classroom watching a YouTube video of a figure dancing. This is no way to form children to look at the world in all its “counter, original, spare, strange” glory, as the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins puts it.[4] Rather than being taught to see through the optical lenses of the frictionless world of online (mal)attentiveness, children deserve a model of education that offers real, tangible things, not merely to satiate but to stretch.

There is a slowly rising tide of pushback beyond our small community in Cambridge. For the philosopher James Williams the “liberation of human attention may be the defining moral and political struggle of our time.”[5] Some say that the answer is for individuals to exercise greater discipline, but for Williams, it is environmental changes that will really make the difference.[6] Schools need to be spaces that resist the kraken-like tentacles of the digital age. Movements for smartphone free education are right and good, so too are efforts to introduce “forest school” and outdoor learning. It is in the interests of these digital evangelists to make it an individualised choice; we must push for collective and systemic action. As Charlotte Mason writes in Home Education (1886): “It is impossible to overstate the importance of this habit of attention … and should be made the primary object of all mental discipline.”[7] Mason calls attention a habit that must be cultivated, but habit is itself a discipline that is made harder by the plague of attentional anaemia.

When summing up his work on attention, the American philosopher and psychologist William James[8] writes that no matter how scatter-brained a person may be, “if he really care for a subject, he will return to it incessantly from his incessant wanderings.” At the heart of attention, for James, is care. There is a way to ensure that the children in our care avoid being ensnared in this similar web of our own making. What educationalists must do is to offer a full and brimming vision of learning and of formation. This includes a vision of education that builds on the vision of figures like William James and Charlotte Mason. The educational vision that holds before the child an encyclopaedia filled to the brim with exciting and enticing facts, which requires their effort and perseverance, that draws them toward the good is the better way. We fail something in their very person if we serve them a bland and tasteless meal, rather than an abundant feast.

Toby Payne is a primary school teacher at Heritage School, Cambridge. He recently completed an MEd looking at the philosophy of attention in the Digital Age.

[1] Charlotte Mason, An Essay Towards a Philosophy of Education (1923, reprint Wheaton, IL: Tyndale, 1989), Preface.

[2] Antón Barba-Kay, A Web of Our Own Making (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023).

[3] Barba-Kay, A Web of Our Own Making, 241.

[4] https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44399/pied-beauty

[5] James Williams, Stand Out of Our Light: Freedom and Resistance in the Attention Economy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), xii.

[6] In Johann Hari, “Why You Can’t Pay Attention,” Primer (2022).

[7] Charlotte Mason, Home Education (1886, reprint Nevada: New West Press, 2023) 146.

[8] William James, “Talks to Teachers on Psychology,” The Atlantic (1899).